Sitting in the car last night on the way back from the office in yet another third-world city, I was musing on the fact that while a lot of people think that the life of an aid worker is terribly glamorous, the reality may be a little different.

Enjoy…

The Perception

6.00 am. I awake to the sound of birdsong. It is the dawn chorus of bowerbirds and migrating swallows as the orange sun breaks above the lip of the savannah grasslands and casts long shadows in dry yellow grass, kissing the bark on spiny acacia trees. The air is warm and dry but fresh with new morning, and the light is casting patterns on the wall of my canvas tent as I slip out from underneath the rustling white shell of my mosquito net.  Beyond the stick fence of our field base, the sound of children singing as they descend to the river to fetch water rouses me into the moment. I emerge from my tent in flipflops and pad over to where a plastic shower-bag is hung in a small wood-walled enclosure that gives some semblance of privacy beneath the open bulb of pale blue sky overhead. The water, still lukewarm from when the sun boiled it yesterday, washes the night’s sweat and grime from my skin and refreshes my soul.

Beyond the stick fence of our field base, the sound of children singing as they descend to the river to fetch water rouses me into the moment. I emerge from my tent in flipflops and pad over to where a plastic shower-bag is hung in a small wood-walled enclosure that gives some semblance of privacy beneath the open bulb of pale blue sky overhead. The water, still lukewarm from when the sun boiled it yesterday, washes the night’s sweat and grime from my skin and refreshes my soul.

6.35 am. Our camp cook fries baked beans and gammon steak on a cast-iron griddle above a woodfire and the white smoke twists into the sky while I check email on my laptop using a portable satellite dish resting on the hood of a once-white Toyota Land Cruiser that is now stained with red dust. I am sipping a mug of overboiled Lipton tea with condensed milk and enough sugar to bury an impala. Past the entrance to the compound, a herder is driving a small flock of speckled goats to the watering hole and their hooves kick up a small mist of dust that hangs in beams of sunlight. Their soft bleating is the soundtrack as the cook beckons us to sit on logs of wood to eat our breakfast.

7.10 am. We’re on the road. A pair of four-wheel-drives and two large cargo-trucks bounce along a rutted four-wheel drive track. It’s the dry season, so it’s hard as cement. During the wet season this is three feet deep in sticky red mud. Tobias is my driver, guide and translator, but today I’m giving him a break and taking the wheel. From beneath the sleeves of my t-shirt my arms are tanned from the sun. Around my wrist I’m wearing a string of beads and shells that was given to me as a gift by the son of a Dinka chieftain when I finally left their village. It confers on me the honorary title of Prince of Bul-bul, but I reflect with fond nostalgia that that’s half a continent away now. Tobias is trying to teach me some more Kiswahili and finds my efforts amusing. There’s a tape in the deck of Amharic music, wailing and screeching and made worse by the scratchy recording getting knocked around by the rough road. It was a gift to Tobias by the former base manager, an Ethiopian whose music Tobias has come to love.

9.20 am. We stop and regroup atop a low rise in the sahel. Our only landmarks are acacia trees and tall trunk-like termite mounds. I pull out my Garmin GPS and wait for it to pick up the satellites. Where we’re going next there are no streetsigns, and we want to stay within the confines of a certain band to make sure we don’t find landmines. A companion NGO, Action to End Mines, assures us that the area has been well cleared, but who really wants to take chances when you’re talking about high explosives? Over in the distance among the grasses we can see a herd of giraffes meandering slowly towards a nearby watering hole.

9.20 am. We stop and regroup atop a low rise in the sahel. Our only landmarks are acacia trees and tall trunk-like termite mounds. I pull out my Garmin GPS and wait for it to pick up the satellites. Where we’re going next there are no streetsigns, and we want to stay within the confines of a certain band to make sure we don’t find landmines. A companion NGO, Action to End Mines, assures us that the area has been well cleared, but who really wants to take chances when you’re talking about high explosives? Over in the distance among the grasses we can see a herd of giraffes meandering slowly towards a nearby watering hole.

11.10 am. We reach Inika, a wretched little village of mud huts and thatched roofs scratching a living from the dust. Men from the village block the track, armed with hoes and clubs. We bring the convoy to a halt and I get out to talk to them. They gather angrily but don’t touch me, noting the logo on my shirt that identifies our organization. I hear muttering. The men are skinny but I don’t fancy my chances against twenty of them. Then the chief comes forwards. He’s a wrinkled man whose brow is largely hidden beneath a heavy white turban. Tobias is standing at my side uneasily, and we’re both sweating lightly under the hot sun. Tobias and the chief talk, and Tobias relays his words to me. The village hasn’t had any food for weeks and is tired of seeing aid convoys going straight through without giving him anything. He says if we try to pass, they’re going to loot the trucks. I look him in the eye and nod earnestly.

“Tell him to wait,” I tell Tobias. Then I go back to the truck, pull out my Iridium satellite phone, and talk seriously for several minutes. The coversation is heated, but finally the chumps back at the national coordination office get the idea. I return to the group of restless men, who are looking at me with some suspicion, not to mention the large phone I’m still carrying in my hand. The chief has a look of mild impatience in his eyes.

“Just tell him to wait,” I say again, a cheeky gleam in my eye.

11.55 am. Most of the village have retreated to the shade of thorn trees, looking listless and fragile. The sun is cooking down, and all we can hear is crickets whining in our ears. My sandalled feet are dusty and my skin burns where shafts of sunlight find their way past branches. A few hardy blokes still block the road. The drivers are lying in the narrow band of shade beside the trucks, too nervous to approach the wary villagers, and nobody’s speaking. The Iridium satphone rings. I listen for a while, then say,

“Roger, wilco.” I turn to Tobias. “Tell the chief to make sure everybody stays away from the grassland at the eastern edge of town.”

He looks at me, nods knowingly, then says something to the chief. The chief eyes me with more suspicion from beneath his turban, but says nothing.

12.05 pm. The rumble of four turboprop engines builds into a roar, and suddenly everybody is on their feet, looking up at the sky and pointing excitedly. Four parallel smudges of dark exhaust hang in the wake of a large Hercules cargo plane, painted white with the blue World Food Organization logo splashed on the tail. It swings low over the village, its tail drops open, then like sparkling raindrops, white sacks tumble from the cargo-ramp.  The air shudders with the screaming engines and dogs and goats scamper for cover, and then the plane is gone again, mere seconds later. The whole operation takes barely twenty seconds. I walk nonchalantly behind the mob of men and women who have suddenly surged forwards, laughing and shrieking with excitement, and follow their stragglers to the edge of the village. By the time I reach the edge of the field with Tobias about four minutes later, the first of the stronger men is already returning with a fifty-kilo sack of grain over his shoulder, grinning from ear to ear. We catch sight of the chief a moment later, and he comes up and dips his head in appreciation, murmuring words of thanks. I look at Tobias.

The air shudders with the screaming engines and dogs and goats scamper for cover, and then the plane is gone again, mere seconds later. The whole operation takes barely twenty seconds. I walk nonchalantly behind the mob of men and women who have suddenly surged forwards, laughing and shrieking with excitement, and follow their stragglers to the edge of the village. By the time I reach the edge of the field with Tobias about four minutes later, the first of the stronger men is already returning with a fifty-kilo sack of grain over his shoulder, grinning from ear to ear. We catch sight of the chief a moment later, and he comes up and dips his head in appreciation, murmuring words of thanks. I look at Tobias.

“He says we can continue,” Tobias tells me.

2.25 pm. We reach the Kirapo refugee camp with our two trucks. A surge of cheering refugees rushes towards us in colourful robes as they catch sight of the flags flying from our trucks and we’re instantly surrounded. I manage to force the door of the Land Cruiser open and wade into the crowd, while hands reach out to touch me, to feel the unfamiliar texture of my clothing, to brush my hair with their fingertips and feel white skin beneath their pink pads. It is claustrophobic and devilishly hot, but I manage to get around to the back of the trucks, where I clamber up and with Jonah beside me, we lower the trailer and start throwing aid parcels into the crowd. Each one is plucked from the air by laughing, joyful refugees.

3.00 pm. The parcels are almost all handed out. There are maybe a hundred left, still tucked at the back of the truck, and the crowd has now dissapaited. The most powerful of the chiefs in the refugee camp approaches us as we begin to raise the tail of the truck, surrounded by a score of young men. He’s a well-built, proud man with a small round skull-cap and deep wrinkles around his eyes that speak of much weeping.

“Please,” he says in a voice surprisingly gentle for his substantial bulk, nodding to the remaining parcels. “There are the sick and disabled among us who have not been able to stand and receive your gifts. Please allow me to take them to these ones.”

Jonah and I both dip our heads in honor and begin shuffling the last parcels to him.

3.10 pm. The last of the parcels are now gone. Jonah and I lock the tailgate in place just as an elderly woman approaches us. There is a tiny waif of a boy clinging to her colourful hem. Her face is wonderfully creased, her eyes blued by glaucoma and her round wrinkled mouth is toothless save for one remaining chopper which protrudes like an oak in a summer prairie. She has one parcel clutched beneath her arm, and there are tears in her eyes as she reaches out and seizes my hand in both of hers. They are dry like cured leather, warm against my skin as though the nature of the very continent is being channeled through her.

3.10 pm. The last of the parcels are now gone. Jonah and I lock the tailgate in place just as an elderly woman approaches us. There is a tiny waif of a boy clinging to her colourful hem. Her face is wonderfully creased, her eyes blued by glaucoma and her round wrinkled mouth is toothless save for one remaining chopper which protrudes like an oak in a summer prairie. She has one parcel clutched beneath her arm, and there are tears in her eyes as she reaches out and seizes my hand in both of hers. They are dry like cured leather, warm against my skin as though the nature of the very continent is being channeled through her.

“My grandson,” she creaks through a throat cracked with drought, “hasn’t spoken since he saw his parents die when the rebels drove us from our village. But today, when he received your parcel just now, I heard him speak ‘thank you.’”

“Thank you,” the fragile child murmured in echo, as if prompted from the shelter of his grandmother’s robes. And then, as if an apparition from the sands of the desert, the pair fade back towards the domes of makeshift shelters, bowed wooden branches wrapped with silver and blue tarpaulins of the UN Refugee Agency. We stand in honored silence and watch them retreat. But we can’t bask in the tender silence for very long as we still have work to do.

3.40 pm. Huraka camp. We locate the second field team by the towering crane of their water rig, mounted on the back of a flatbed lorry. The machinery is in full tilt, the augar spinning, a churning mix of mud and water where the drill is powering through the earth as pipes are sunk towards the water-table. We pull up near the crowd of onlookers and get waved another hundred yards further on, where we see the other half of the water team. They are bolting the handle onto a pump, the sort that you expect to see in an old farmyard. There is an eager crowd here as well, and as the finishing touches go onto the simple mechanism, a spontaneous choir of women in flowing robes of green and gold and ochre is singing a six-part harmony, clapping their hands and swaying to the music. The final nut is locked off, and the team leader gestures to a wide-eyed boy of about twelve. To the good-natured cheers of the onlookers, he is urged forward and seizes the handle of the pump, driving it up and down several times. After a little while, and still no water coming out, two of the construction team join him, and as a threesome they work the handle until the first splash of crystal-clear water tumbles sparkling from the deep bore, and the women erupt into trills of joy that make our ears ring.

4.45 pm. The road back to Inika. A gang of armed rebels is loitering beneath the shade of an acacia tree in the tracks ahead, Kalashnikov AK-47s waving skywards as they flag us down with gestures laden with confident arrogance. They are in ragged fatigues of no particular alliegance, high on power and thuggery. We slow carefully and approach them with the windows down, and they order us out of the car.

Their leader approaches. He’s the only one with a cap, and it has a set of brass oak-leaves pinned to the middle, but I doubt he’s a real Colonel. He is older than the teenage boys around us, and has a swagger that outdoes the rest of them combined. His shirt is open to the last two buttons above his waist, and he likes to get right into my personal space. I can smell what appears to be ethanol on his breath. Tobias translates, and I listen.

Their leader approaches. He’s the only one with a cap, and it has a set of brass oak-leaves pinned to the middle, but I doubt he’s a real Colonel. He is older than the teenage boys around us, and has a swagger that outdoes the rest of them combined. His shirt is open to the last two buttons above his waist, and he likes to get right into my personal space. I can smell what appears to be ethanol on his breath. Tobias translates, and I listen.

“He says we can’t go through until we pay him bakshish.”

I inform him we’re an aid convoy and have nothing to give him

“Then he says we can’t go anywhere. He’s impounding the vehicles for being in breach of code 148, section C.”

I want to look him in the eye and tell him I know he’s just made that up, and that the rebel commander has reached an agreement with the UN to let NGO vehicles pass, and that if I make a big deal of this later he’ll find himself in front of a firing squad next week

But I don’t.

Instead, I reach into my top pocket where I have a packet of Benson & Hedges Gold. I don’t smoke them myself, but I keep them for times like these. With a steady hand I look him in the eye and offer him a smoke, and he looks at the pack hungrily. Then I pass them around the rest of the motley crew, most of whom would still be in middle-school back home. When the leader signals for a light, I have one handy in my pocket and strike him up, then pass him the lighter and indicate he can keep it. His eyes mellow as he takes a puff of white smoke, and just to fit in, I stick a cigarette between my own lips but leave it unlit, then reach forward and tuck the box with the last remaining fags into the top pocket of his olive shirt. He beams.

I wait until the boys are all busy lighting their cigarettes, and then I reach into my back pocket and pull out the compact but now-ragged field-guide to International Humanitarian Law. With Tobias at my side, I pull the leader conspiratorially over to the hood of our car, and beneath the curious eyes of the other rebels, I gently explain to him that as neutral aid workers we have the right to help anybody in need, and that to stop us or detain us constitutes a war-crime, so it’s in everybody’s interest for us to keep going. He seems to mull this, sucking back on the cigarette, and finally breaks a big smile, pats me on the back, and we part as buddies. When I look in our rear-view mirror a few minutes later, I can see the boys waving with assault-rifles raised in the air behind a hanging film of red dust.

5.10 pm. We pass back through Inika. As our convoy rolls through, kicking up dust and scattering stray dogs, children run alongside the vehicles, waving and patting the chassis with loud thumps. A small group of them are waiting near the end of the village and as we pass through they break into spontaneous song. I am left with the image of rows of white half-moon smiles in dark faces in my mind as the village rolls away behind us

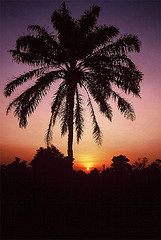

6.30 pm. The sun is an orange globe tangled in the branches of a thorn-tree as our convoy rolls back into the bush compound. I clamber out from behind the wheel, dirty and tired and tingling very slightly after hours of rocking in the vehicle. My body and head both ache and I haven’t eaten since breakfast, but I feel great. I hear the lowing of cattle, and before the last light fades I see a herd of long-horn cows with pale hides and saggy wattles trundle past, under the watchful eyes of two skinny men with long sticks carried across their shoulders, keeping slow, steady pace. Women are returning from the nearby river having washed for the night, and their giggles and chatter makes the warm night feel even warmer

I wash the day’s dirt off under the shower, now scaldingly hot, as the sky turns shades of indigo. While the cook prepares an evening stew of tasty goat, boiled spinach and fried potatoes with onions, I get back onto the portable satellite dish and spend ten minutes informing HQ of our days’ activities. We eat beneath the sky as a thin sickle moon breaks above the peaked tips of our canvas tents, and in the distance can hear the cackling of a hyena. By seven forty-five I am exhausted, and as I head to bed, my last sight of the day is of the Milky Way in all its glory, written across the navy-blue dome overhead. I fall asleep dreaming of the humanitarian achievement award I am sure to win next year…

The Reality

6.00 am. The alarm goes off. I open my eyes and I stare at a ceiling I swear I’ve never seen before. I hear the sound of excessively honking traffic and gridlock and recognize the stark-white detailing of some mid-range hotel in yet another third-world city, virtually indistinguishable from the last. I’m feeling a rough. Probably the combination of a little too much cheap local beer without a confirmed % Vol. rating, and the dodgy sushi restaurant we tried last night around the back of the block. There’s something about raw fish when you’re several hours’ journey from the nearest seaport.

I hit the snooze button and roll over

6.35 am. I’m in the shower. All lathered up with generic hotel-room shampoo that oozes out of the little bottle like that slimey thing from Ghostbusters. I’m standing beneath the spout when the water suddenly runs cold. I don’t react, because it’s happened so many times before, but the little pulse of revulsion it sends through my gut is unavoidable, as I attempt to finish my wash as quickly as possible. I tell myself I really ought to speak to reception about getting my room changed, but I know it won’t make any difference, so I don’t bother.</

7.05 am. The hotel has a buffet breakfast. Dry turkey-bacon, watery scrambled eggs, stale bread for toasting, salty baked beans, fresh buns with little packets of Anchor butter and bowls of jam you never know if you can trust or not. It’s open-air and mild, but the flies aren’t out yet. It’s early, so the clientelle are all professional. There’s a bunch of despondant-looking aid-worker types mixed in with Chinese businessmen and the occasional wizened long-termer, generally white with greying hair, wrinkles, and a red veiny nose. I try and decide which group I least want to sit close to and work through my tea and toast in peace.

7.30 am. My teeth are brushed (I’ve risked using tap-water this morning) and I’m waiting by the front entrance to the hotel for the office driver to pick me up, laptop, notepad and file in the backpack slung over one shoulder.

7.55 am. My driver arrives.

8.25 am. We’re still in traffic. It’s rush hour, and there’s four lanes of moving metal slowly extricating itself through a narrow two-lane intersection. A bus the size of a small ocean-going liner is sitting directly above our rear-bumper, sounding its air-horn and telling us in no uncertain terms that if we don’t move forwards it will turn us into fine and somewhat stained aluminium foil. Two taxi cabs are trying to usurp the two square feet of space in front of us between a produce lorry and an expensive Mercedez sedan with tinted windows. A street vendor is banging on my window and trying to sell me my choice of cell-phone cards or a pack of cigarettes. The driver has the air-con cranked way too high and my finger-tips are actually hurting from the cold, but I’m frightened that if I crack the windows, we’ll both die of carbon monoxide poisoning.

8.40 am. The office elevator is out of order again, so I climb the three underlit flights of stained, grimy stairs that reek of cheap cologne and stale spicy food until I reach the right floor. In the humidity, I’m already sweating and my shirt is clinging to my back, my sides, and the cleft below my neck. I tell myself I need to spend more time in the hotel gym if I can’t handle three measly flights of stairs. I walk in on the morning operations briefing ten minutes late and cop a dirty look from the Office Manager.

8.55 am. We’re back in traffic. We’re sitting at a five-way intersection and the predominate sound I can identify is the honking of horns and the desperate blowing of a police whistle as drivers and a solitary traffic cop try and unravel a knot of vehicles of Celtic proportions. There’s a coordination meeting at the UN offices which we need to be represented at which starts at 9. Nobody told me last night. I watch the clock for a while, then I lean my head against the headrest and recapture some of that rest I don’t feel like I got last night.

9.15 am. I walk into the conference room in the UN. It reminds me of my old school classrooms, a set of cheap low tables arranged in a U-shape at which delegates sit facing inwards. The UN resident coordinator breaks halfway through her briefing to give me a dirty look, and as I slink to the one remaining seat (with increasing memories of school classrooms) I don’t bother to explain to her that half the reason I’m late is the eight minutes it took me to talk my way past the UN security guard because I forgot to bring my passport. I look around the room, and most people are bored and listless. Some are doodling. We’re going over the same bloody territory. Again.

9.35 am. Agencies are giving their updates on behalf of their field offices up-country. The representative of a high-profile French agency stands up and announces to the room in general that she has heard that my particular NGO has been providing assistance to several villages without communicating with the local administrator, with the result that there has been duplication and wastage. She fixes me with the sort of stare Parisiens are trained to develop shortly after birth. It’s the sort of stare that can make mature oaks wither and seasoned wrestlers bead up into tears. When she sits down there is a long, icy silence. There seem to be a lot of eyes watching me, and I wish to join my cheap Bic ballpoint pen in its anonymity on the table at my restless fingertips.

A couple of minutes later, there is a power-cut and the lights go out, and the hum of the split-system air conditions rattles to a halt. Nobody looks up.

10.10 am. We’re heading back to the office. Parliament are sitting today, and the police have closed off one of the main thoroughfares until all the members of parliament have passed through. The driver doesn’t expect us to move for at least half an hour. We don’t.

10.55 am. I’m at a corner cubicle in the office, the only one they had available for me when they knew I was coming three weeks ago. The local adaptor for my plug doesn’t quite fit right and the plug keeps dropping out of contact. When I get down on hands and knees to try and fiddle it back into place, blue sparks sizzle inside the mechanism. I sit back at the desk. The back to the desk-chair I have is buggered and yaws lazily out into space behind me, so that if I lean on it I’ll go right over backwards. I have about a square metre of desk-space between the walls of my cubicle and I wonder how many OH&S violations this would be in breach of back home. I look down at my computer and see that the internet has dropped out again. I’ve had a running battle trying to get the local IT boys to reconfigure the IP address on the laptop I’ve brought from HQ but they can’t seem to navigate the security features that HQ IT have put in place, so it keeps dropping out. But I mention it in passing to a frazzled-looking logistician on the far side of the cubicle and he informs me timidly that the server is out. Again.

11.10 am. The server is back on. I get to my emails for the first time since ten o’clock last night. A wall of red greets me. There are forty-two new messages, including nine flagged ‘urgent’. This is in addition to the red messages I didn’t get through the day before. Or the day before that. I settle in to work.

11.12 am. Message from our Funding Office in the UK. There will be some changes to the emergency water grant we’ve received from the British Government. Due to exchange-rate losses they’re cutting the agreed budget to seventy percent of the total, even though last week we pushed through the purchase of three water tankers, the chief capital assets. Also, they want us to include activities that specifically target pregnant women with physical disabilities. Also, about those tankers, they want us to come up with an asset disposal plan that will pass the tankers on to the district government office to ensure ‘sustainability’. I knew this was coming. I raised it with the office two days ago and pointed out that the district governor was as bent as a four-pound note.

“I know, I know,” my counterpart replied. “But they think it looks good for the relationship between countries, you know. You need to appreciate their context.”

11.18 am. Message from our Funding Office in the US. They’re having some trouble with the food distribution grant we’ve received from the US Government. Seems we can only distribute US-produced food under a US Government grant. They’ve helpfully included a list of brokers two countries over who import US-produced staples. I note that this will triple our transportation cost and that the suppliers stock yellow maize, not white maize which is what people eat here.

11.21 am. Another message from our Funding Office in the US. We forgot to fill out the form that confirms that none of the partners, suppliers, transporters or community-based organizations we work with (in this or any other project) match with the US Government Terrorist Watchlist. I open the attached Excel spreadsheet and there are 987 entries to cross-check.

I close the Excel spreadsheet.

11.25 am. Message from our Headquarters. They’ve been pushing through changes to the timesheet process. There’s a brand new Access database-based spreadsheet which will enable us to account for our time in fifteen-minute blocks throughout the work day, in eighty-one different categories. There is web access specifically set up for staff travelling overseas, so there’s no excuse for deployed staff not to fill in their timesheets. There’s a URL that will take me straight to it.

I don’t click the URL.

11.32 am. Message from our Fundraising Office in Germany. Commenting on the response strategy document I put out last week. The strategy was the result of three weeks of work, including six iterations that went through nine key stakeholders internally, three at our regional office, representatives from four different fundraising offices and two technical working groups in headquarters. The Germany Office is concerned we’re putting too much emphasis on focusing on crisis-affected people with HIV/AIDS. This is supposed to be an emergency, and HIV/AIDS will wait for six months.

11.34 am. Message from our Headquarters technical working group on HIV/AIDS (who weren’t involved in the strategy consultation process). The strategy doesn’t have enough focus on HIV/AIDS. Don’t we realise that HIV/AIDS is a critical issue in any situation where displaced people are involved due to the high risk of spreading through increased sexual activity that accompanies these contexts?

11.35 am. I close the lid of my laptop, less than halfway through my emails. There’s a water-cooler in the staff kitchen, but the blue 5-gallon bottle on the tower is empty and nobody has ordered a replacement. I loiter in the kitchen until the smell of old food in the garbage bin mingles with the heat and starts to make me feel unwell.

11.40 am. Message from our Fundraising Office in Japan. The monthly activity report we sent through for their shelter grant didn’t have any decent photos to show the donor. They want to see photos of the relief tents, with our logo clearly evident in the shot. This is the third time I’ll have explained to them that the government doesn’t allow cameras in the camps.

11.42 am. Ping. I have a new email. It’s a press release from our Fundraising Office in New Zealand about our crisis. They’ve circulated it around to all the internal stakeholders, letting us know that it went out to their media outlets yesterday around midday and was posted on their webpage. They’re slamming the government for breaches of human rights in their fight against the rebels, and also claim that the UN is doing a poor job of coordinating the response and that huge needs are being left unmet in the camps.

I close my eyes and rest my forehead against the top of my laptop.

11.48 am. The Emergency Manager walks past my desk and we lock eyes. He’s just seen the same email. We shake our heads and say nothing.

12.05 pm. Communal lunch is being served in the kitchen. It’s some curried stew and I can smell it from my desk. I don’t really want much, but I figure I’ve got a lot lined up to do this afternoon and if I don’t eat something now, I won’t get anything. When I help myself to the stew, it’s not all that hot, so I take a fairly small portion and add some rice and finish lunch standing up in the cramped little kitchen while people jostle my elbows. The meat is some variant on goat, with lots of gristle and fat, and the sauce is greasy; I can see the blobs of oil floating apart from the watery broth. It tastes a little funny to me.

12.55 pm. I’m with the Emergency Manager, discussing how we get our message through to our Japanese Fundraising Office when the telephone rings. The Emergency Manager picks it up and his face falls. Even across the desk from him I can hear the voice yelling down the line. It’s the Government Humanitarian Coordinator. He wants to see us in his office in one hour.

My stomach makes some funny churning noises, and I’m not sure if it’s the goat stew, or the thought of being yelled at by the Humanitarian Coordinator. Again.

1.10 pm. On my way down stairs I run into the grant accountant whose supporting our team finances.

“I put in a reimbursement claim for last month’s field trip nearly two weeks ago,” I tell him. “Can I have my cash?”

He explains stiffly that I didn’t have receipts to back up all my expenditure so they haven’t processed my forms.

“You had some transport expenses which weren’t properly supported.”

“Transport?” I growl at him. “I was using tuk-tuks. The drivers don’t have receipts. They’re illiterate!”

“I realise that. But we have to have paperwork. You need to understand our context.”

Before I can set on him, the Emergency Manager is tugging on my sleeve. We need to get across town.

1.20 pm. Traffic.

1.35 pm. Traffic. About three blocks further down. It would have been quicker to walk.

1.35 pm. Traffic. About three blocks further down. It would have been quicker to walk.

1.45 pm. We’re sitting on a sunken brown couch in a hallway in some minor government administration building. It has no springs left and is the sort of thing that my buddies might put in their basement den after finding it at a yard sale, cover with an old bedsheet, and drink beer while watching the hockey. In front of us, men in suits are striding up and down the corridors trying to look important, their footfalls echoing between the bare walls. Cheap wooden doors have brass nameplates on them. There’s no air-conditioning and the place smells vaguely of detergent and cigarette smoke.

1.55 pm. The Humanitarian Coordinator knows we’re out here. We know he’s in there. We know he’s in there alone, and that he’s not doing anything useful, except maybe putting some purple ink-stamps on various pieces of superfluous paperwork so that he can justify drawing a salary in the name of frustrating the international community’s efforts to help his people. But he’s going to keep us sitting out here for, ooh, another five minutes I reckon. Just because he can.

My stomach is making gurgling noises.

2.00 pm. The Humanitarian Coordinator opens his office door and beckons us in with a hand-gesture. He’s a rotund man with skin pulled tightly over a round face, a deeply threaded forehead and floppy jowls. His default expression is scowl, and he’s in default mode. He sits us down not out of politeness but because it’s easier to snarl at us when we’re seated. He goes around to his side of the desk, pulls out the press release that our Funding Office in New Zealand published, and waves it in our faces while threatening in a loud voice to revoke our permission to work in his country.

This continues for about fifteen minutes, and I try and look chastised while my Emergency Manager makes cooing, apologetic noises.

My stomach starts to cramp sharply.

2.17 pm. My stomach tightens again and I flinch in my seat. I realise with horror that I’m not going to be able to wait until the Humanitarian Coordinator is finished. I stand up apologetically, ask where the bathroom is and hope desperately that I’ll be dismissed as some stupid white man, rather than cause grave offence that will result in our program here being shut down. He pauses, scowls, then waves me out of the door. I virtually sprint from his office, scan desperately up and down the hallway, take my chances to the left, and luck out about ten doors down when I find a bathroom.

It is dirty and there is water all over the floor and all over the seat. It smells feral. There’s no paper, just a little hose-pipe nozzle on the wall. Right now I don’t have time to worry about this. I barely reach the seat in time for my stomach to indicate exactly how it feels about the goat I had for lunch.

2.24 pm. The worst is over.

Oop… wait… no it isn’t.

2.28 pm. I find myself wondering whether the Emergency Manager is still in the office with the Humanitarian Coordinator. I begin to ponder the toilet-paper dilemma.

2.29 pm. My cell-phone rings. I look at the screen. It’s the UN resident coordinator. I let it ring off. A minute later, she is ringing again. I know she wants to yell at me for the press release as well. I let it ring off again, then when it stops ringing, I switch my phone off and drop it back into my pocket.

2.34 pm. I emerge from the toilet. My dilemma has been solved by reaching a compromise I’m not prepared to talk about, nor will I be until after several expensive sessions of counselling. I can’t face the Government Humanitarian Coordinator again right now, so risking expulsion from the country I limp back down to the Land Cruiser waiting outside the front gate. The Emergency Coordinator is sitting in the front seat on the telephone, looking grim. He hangs up just as I get in.

“That was the UN resident coordinator,” he tells me. I just nod. Neither one of us says anything.

2.50 pm. Traffic. Schools are emptying and the place is crammed with vehicles of all sorts, not to mention kids running between gridlocked vehicles.

My stomach churns, and I start to pray.

3.25 pm. We make it back to the office and I make it as far as the second floor before branching out to find the nearest toilet.

3.40 pm. I am back at my desk, sweating lightly. There are eighteen new emails since lunch. I scan them and try and prioritise the issues. There is the activity report from two weeks ago, five days late. Its content is woefully inadequate. I reach for the telephone just as the power goes out. There aren’t many windows up here, so my laptop screen glows eerily. The hum of air-conditioners fades, and I find myself wondering how long the power will be out for this time. I look and see that I have 1 hour and 58 minutes of charge on my laptop battery. Most of the local staff are using desktops and only a few of them have Uninterrupted Power Supply units, which are now beeping noisily to warn the world in general that the power is off. At least I can still work.

Lucky me.

3.46 pm. After six tries, the line finally goes through to the Field Manager. He speaks to me in short, persecuted sentences. When I raise the issue of the report with him, he finally snaps and says,

“Look, it’s all very well for you in the capital with your power and your internet and your air-conditioned cars to take you around town. It’s different up here. You just don’t understand our context.”

I was there with him ten days ago and helped him draft the framework for the report, but he clearly can’t remember that far back. Given the state of things up there right now, that may well be the case.

4.10 pm. The Emergency Manager comes over and fixes me with a cold eye.

“That was the US Embassy. The Emergency Rep has been trying to reach you for an hour and a half.”

I remember that my phone has been off for the last two hours. I switch it back on and see eight missed calls. Six of them are from the US Embassy. My stomach churns again, but this time it has nothing to do with the goat.

4.25 pm. The electricity is still out. The air is hot and close and smells are drifting in from the street. It feels like I’m trapped in a small plastic bubble in the middle of Ethiopia, accompanied by a dead horse.

4.40 pm. The electricity comes back on with a spurt. There are comments of relief. But the air-conditioners stay off. Somebody’s computer has been fried by the surge as the power comes on. But I can still work.

Lucky me.

4.45 pm. Tech support inform us that a circuit has blown downstairs and they have to call an electrician. I overhear one staff member tell another that the last time this happened it took them two days to get it fixed.

My stomach is rumbling again.

5.00 pm. I call another of our Fundraising Offices. They’re just coming online now, courtesy of time differences. They were supposed to give us two million dollars to support a multi-sectoral response program, but three days ago they axed it by fifty percent, claiming the money had been moved to other priority areas.

“Look,” I say, “We’re really in a rough way up there. The proposal’s all ready to go, but we need that cash.”

“It’s gone,” my counterpart replies, not without some regret. “Sorry.”

“But, how? You told us you had two million.”

“Things change, I guess.”

“Well, can’t you get us some more?”

“Like how?”

I don’t point out to him that it’s his job to figure that out.

“Why don’t you run an appeal?” I suggest.

“We can’t.”

“Why not?”

“Look man, you don’t understand our context, okay?”

5.45 pm. I finish going through most of my emails. My eyes are hurting. The air is stifling and my shirt has started to grow into the skin of my back. The office is starting to empty, except for the emergency team who are all huddled in silence over their laptop screens.

5.55 pm. The Emergency Manager calls us over for a team meeting. We gather, red-eyed and harried, in a little knot in the corner of the office. I look from face to face and we each look like we have been through our own personal version of hell today. And every day for the last three weeks. The Manager begins to list of the things that need to get dealt with, and we begin to add to the list, but we’re too tired to come up with solutions and nobody’s got the wherewithall to take minutes. A lot of these issues are starting to sound terribly familiar. Are we sure we didn’t talk about them the day before yesterday…?

6.55 pm. I’m leaving early. I’m meeting the US Embassy Emergency Rep to talk about a proposal over dinner at the hotel. Clearly the guy wants to get this money spent or he’d have blown us off already. Either that, or the Emergency Manager did some fast talking. I head downstairs to the vehicle pool, but all the drivers have gone home, so I plod down to the street and flag down a cab driver.

6.55 pm. I’m leaving early. I’m meeting the US Embassy Emergency Rep to talk about a proposal over dinner at the hotel. Clearly the guy wants to get this money spent or he’d have blown us off already. Either that, or the Emergency Manager did some fast talking. I head downstairs to the vehicle pool, but all the drivers have gone home, so I plod down to the street and flag down a cab driver.

The driver eyes me up and sees a walking wallet. I tell him the name of my hotel. He nods and waves me in to his vehicle.

“Meter,” I say, telling him to turn his meter on. He shakes his head with an apologetic smile.

“No meter. Meter break,” he says, and names me a price that is four times the going rate. I know his meter works just fine. Unfortunately most of the meters in this town seem to be afflicted with a problem that whenever a person with white skin climbs in, they inexplicably stop.

I managed to talk him down fifty percent, and off we go.

7.25 pm. We’re in traffic. The cab has no air-con and the windows are cracked but not open. It’s enough to get doused in the choking scent of gasoline fumes, without any semblance of moving air. I feel wretched.

7.45 pm. I don’t even bother to go up to my hotel room. I’m fifteen minutes late for the meeting with the Embassy Emergency Rep. I waltz into the buffet dining area with my backpack and my sandals, my jeans grubby and my shirt disheveled and still sticking to me in places. I feel like I’ve just run a marathon, when actually the most I’ve strained myself all day (with the exception of my time on the toilet) was a particularly spiteful strike of the ‘enter’ key at the end of a bitter email. The donor is unimpressed with my tardiness as I approach the table with a gaze I hope communicates a balance of contrite apology and sympathy-inducing brokeness. He just fixes me with a look that says ‘I have four million dollars at my beck and call; you clearly have a hard time getting your office to pick you up on time.’

“We want to help you, really we do,” he says as we talk. “But we need you to be ready to come to the table when we snap our fingers. Work with us here. You gotta understand our context.”

With a lot of grovelling and some creative application of the truth, we walk away with a shot at submitting a proposal, which needs to be in in the next seventy-two hours.

9.45 pm. I stagger up to my hotel room, dump my backpack and lie face-down on my bed for a while as the ceiling-fan cools my sweaty back. There’s a cricket under my wardrobe and it starts to chirp after I’ve been still for about two minutes. It did that last night as well. At two am. Then at three am. Then at four. I can’t find it, or else it would be in many tiny and very flat fragments of exoskeleton right now. I know it’ll do the same to me again tonight, but right now I don’t have the energy to do anything about it.

10.05 pm. There’s no hot water at all, but I’m beyond caring. I let the water wash the grime and sweat of the day away and almost forget to turn the water off.

10.07 pm. I flick off the lights. Sleep at last. The next eight hours at least are mine and nothing’s going to take them away from me.

10.14 pm. The cricket starts chirping. For two minutes I pretend I can block it out. Then I’m up and out of bed. Lights on. Sandal in hand. I know it’s under the wardrobe, the little bugger. For a couple of minutes I try and flush it out. Then I just go for it. I drag the wardrobe away from the wall, and there it is, black and squat and smug and smirking at me. I pound it into a fine paste, leave the wardrobe at a thirty-degree angle to the wall, kill the lights, and collapse into bed.

At last.

10.27 pm. Asleep.

10.36 pm. I’m back on the can. The goat is back for an encore…

Really interesting read, Tris. In my opinion even better than your regular photo-posts. I guess if there was a commercial company working the way you described, it would sooner or later go bankrupt, leaving room for another one or two to emerge. Ones that would let their employees focus on the job. Too bad this doesn’t apply to (inter-)government agencies.

Thanks for your feedback mate and glad you enjoyed. I need to point out that both sides of the coin in this account are somewhat fictionalized- the latter less-so than the former however! It’s true- commercial companies couldn’t operate the way NGOs do, but then sadly, there’s little scope for for-profit orgnizations to operate in humanitarian aid. Helping people just doesn’t make the big bucks, so it’s left to the rest of us to try and muddle it through. Truth be told, it’s a hugely complicated sort of operation to run. When you’re driven by the Bottom Line, it’s easy to streamline your work processes. When your modus operandi is stakeholder management and an aetherial concept such as ‘quality of life’ then trying to identify your end-point and incorporate the needs, wishes, motivations and politics of other parties to what you’re doing becomes a daunting task. We need to take into account the desires of the people we’re working for, the drive of our donors, issues of ethics and human rights as paramount, and to work alongside literally dozens of other organizations all of whom are trying to do similar things, and yet operate within a frequently high-restricted national or military context where what we’d like to do has to be negotiated every step of the way. And do it all with teeny-tiny budgets (relative to what we need to accomplish) which are constantly getting stretched, all while detractors are waiting for us to slip up so they can criticise us: for being too outspoken against the government, for being too complicit with the government, for not reflecting the needs of beneficiaries, for not incorporating this standard or that standard, for not coordinating enough, for wasting money… *sigh* Maybe I should have been a banker like my grandfather…

Tris..

The mention of your blog last night reminded me of this piece, which I read way back when you posted it and remissly failed to comment on. I say ‘remissly’, because it made an impression I feel I need to reflect back to you.

I really LOVED this snap-shot. Particularly your very humorous, humble and humane reflections of the Reality of your work. The recount of this ‘typical day’ evoked a response from every spectrum of the emotional rainbow for me. I laughed and cried and cried with laughter. I also gained a real appreciation for the idea that each stakeholder in an issue that you/your agency is handling has proverbially tied a rope to one of your limbs and is driving off in a different direction. Making matters worse, your body has it’s own responses to the situation or more specifically, to lunch (priceless). It really is just as well you enjoy a challenge.

The fact that you deal with predicaments of such epic proportions… then find yourself dealing with yourself… then admit to this, is at once both admirable and accessible.

Thanks for the insight!

Thanks so much Ambs. It’s not only lovely to hear back that people are reading through this stuff, but also means a lot to hear that people respond to it within themselves. I guess when I pen this there’s a mix of stuff going on. Part of it is for my own catharsis. Part is wanting to entertain. A big part, honestly, is probably a narcissistic desire to let people know what’s going on with me. And part is to give people the opportunity to come with me a little ways on the journey and see the world from my eyes. I’m really pleased you were able to come on that journey a bit, and that it touched you. You’re always welcome. ;o)

(and I really like that image of having ropes tied to various limbs all heading off in different directions… a thoroughly apt metaphor! 🙂 )

Oh my. Your blog post has put my false perceptions to shame.

I didn’t think aid work was as idealistic as you initially described… but the latter just sounds like hell. How do you manage?

Looks like I’ll have to keep rethinking my career goals!

Pingback: 5 Part Series: Becoming an Aid Worker « WanderLust

Thanks for sharing!

really you just sound like a whiny douche. negative about everyone and everything. no one spared.

“they” must be so lucky to have someone like you. if only “they” knew how much help you are bringing.

Well, it’s a good job “they” have a sense of humor, or we could all be in a lot of trouble.

You are obviously trying to get a book deal, when what you should get is fired. What an attitude.

Who’s forcing you to do this?

I was pointed here from another blog. I think their commentary is spot on, so I’ll link it in hopes you’ll read.

http://mungowitzend.blogspot.com/2011/07/day-in-life-of-worst-aid-worker-in.html#links

The TL:DR version is that you should stop complaining about first-world problems when you’re in the third world. How do you manage, indeed.

Scottyboy, bob, marecha — it’s amazing how validated you can feel when you can create endless allies to back your trolling.

Carly shared this with me the other day. Bloody hilarious. Never mind this lot T…

Why don’t you get more respect, more status, more freedom, more perquisites, more glory, more authority, more money, more appreciation, more sympathy?

Did you once show concern about doing those things for others?

Pingback: What is an Aid Worker and How do I Become One? | The Out Post

Pingback: Ulterior Motives: Part 2 | UpLook

Just came across your blog. I can’t stop reading. Love the juxtaposition of this post. So true! Keep it up.

Thanks Dan for your kind words- and glad you enjoy. You’re always welcome! 🙂

Brilliant – your latter version is spot on. Reading it put so humorously (when you think it might be one of those break-down-and-cry days) has really made my month. Back to do it all again tomorrow!! 🙂

I really loved this post, and I love your candor, humour and authenticity. Thanks for sharing.

To those attention-seeking idiots above who would obviously be the AWESOMEST AID WORKERS EVER x 1000000 if they were in your position, congratufuckinglations for having no sense of humour or appreciation of reality whatsoever. Please send photos when you sail off to single-handedly save the world Angelina Jolie-stylie.

To the author – keep on keeping on.